과다환기 유발 부분운동발작으로 방문하여 모야모야병으로 진단된 3세 남자 환자

Moyamoya disease in a 3-year-old boy presenting with a focal motor seizure provoked by hyperventilation

Article information

Trans Abstract

A previously healthy, 3-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with an afebrile focal motor seizure. He was found crying and having a seizure 30 minutes earlier. During this seizure, he was jerking his head and right extremities. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging showed acute infarction in the bilateral frontal lobes, chiefly in the left. After hospitalization, conventional angiography demonstrated bilateral stenosis of the distal internal carotid arteries with development of lenticulostriate collaterals, which confirmed the diagnosis of moyamoya disease. It is vital to recognize focal motor seizures and situations related to hyperventilation in children with a seizure, which imply a structural lesion and a provoked cerebral ischemia in preexisting moyamoya disease, respectively.

Introduction

Moyamoya disease (MMD) is an idiopathic vasculopathy characterized by progressive occlusion of bilateral, distal internal carotid arteries and consequent development of lenticulostriate collaterals. MMD accounts for 6% of childhood ischemic strokes [1], and is more common in East Asia [2]. The most common presenting symptom of MMD is hemiparesis [2]. However, 11%‒27% of children, especially toddlers, present with seizure [3-7]. Diagnosis of MMD should be expedited in the emergency department (ED) because surgical revascularization reduces the risk of stroke from 80% to 4% [1]. This report describes a 3-year-old boy with MMD who presented with a focal motor seizure possibly provoked by hyperventilation.

Case

A 3-year-old boy with an ongoing seizure was brought to the ED. During the seizure, his head was jerking to the left, the eyes were deviating upward, and the right extremities were jerking (Supplementary video 1, https://www.pemj.org/). This lateralizing sign suggested a structural lesion in the left frontal lobe. Although he was initially alert and crying, he became unresponsive as the seizure progressed. There was no immediate history of febrile illness, head injury, intoxication or vaccination.

Thirty minutes earlier, shortly after falling asleep, he was found having a seizure and crying. Until the arrival at the ED, he had undergone a total of 3 ictal episodes, each lasting 1‒4 minutes, with incomplete recovery of consciousness between the episodes. Given the frequent recurrences within 30 minutes, he was considered to have status epilepticus, and received intravenous lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg) and fosphenytoin (20 mg phenytoin sodium equivalent/kg).

He was born as a monozygotic twin and otherwise healthy except one episode of febrile seizure, which occurred 2 years earlier during a fight. His mother and twin brother had a history of febrile seizure. No family history was found on epilepsy, brain tumor, and childhood stroke.

The initial vital signs were as follows: blood pressure, 137/85 mmHg; heart rate, 118 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 22 breaths per minute; temperature, 36.3°C; oxygen saturation, 100% on room air; and blood glucose, 96 mg/dL. He weighed 18 kg and was alert and age-appropriately oriented, but he had slurred speech. Neurological examination was limited because of the sedation with intravenous lorazepam and fosphenytoin. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

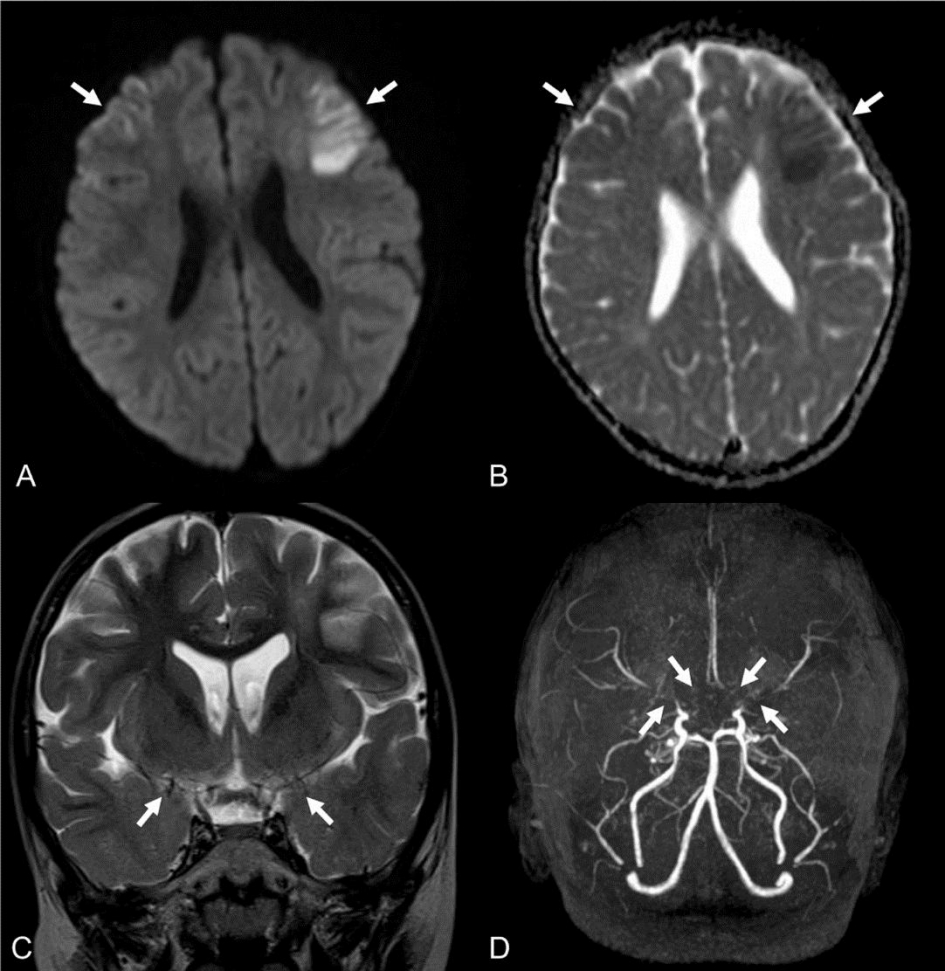

Initial laboratory evaluation showed a white blood cell count of 10.6 × 109/L with 38.3% neutrophils, 53.5% lymphocytes, and 5.2% monocytes. Venous blood gas analysis indicated acute respiratory alkalosis with a concomitant metabolic acidosis with the following values: pH, 7.44; PCO2, 31.9 mmHg; and HCO3, 22.4 mEq/L. Other laboratory findings were normal. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed a high signal intensity in the bilateral frontal lobes, predominantly in the left, and a loss of flow voids in the bilateral middle cerebral arteries, suggesting acute infarction due to MMD (Fig. 1A-C). He was hospitalized in the pediatric neurology unit.

Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography findings showing acute infarction and bilateral stenosis of the distal internal carotid arteries and middle cerebral arteries (MCAs). Axial diffusion-weighted image shows high signal intensity in the bilateral frontal lobes, predominantly in the left (A). There are low apparent diffusion coefficient values in the corresponding areas, which are suggestive of acute infarction (B). Loss of flow voids in the bilateral MCAs on a coronal T2-weighted image indicates diffuse stenosis of the arteries (C). Time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography shows bilateral stenosis of the distal internal carotid arteries, and occlusion of the bilateral M1 segments of MCA and A1 segments of the anterior cerebral artery (D).

On day 1, he was found having right hemiparesis involving the arm and leg with muscle strength of 4/5 and right central facial palsy. An aspirin regimen (5 mg/kg/d) was initiated. Electroencephalography without a provocation maneuver indicated interhemispheric dysfunction. On day 4, magnetic resonance angiography showed bilateral stenosis of the distal internal carotid arteries (Fig. 1D). Conventional angiography confirmed MMD on day 5 (Fig. 2). No findings indicative of hypercoagulability, vasculitis or metabolic disease were found. Echocardiography was normal. On day 8, he was discharged with slightly improved hemiparesis (muscle strength of 4+/5) and facial palsy, after consulting with the neurosurgery department for revascularization. After discharge, he was found to have RNF213 single nucleotide polymorphism with heterozygote c.14429G>A (p.R4810K) variant. A few days after the presentation, his monozygotic twin brother was brought to the ED for having a seizure, and found to have MMD with the same genetic feature.

Conventional digital subtraction angiogram showing bilateral stenosis of distal internal carotid arteries (black arrows, A and B) and leptomeningeal collaterals characterized by “puff of smoke” appearance (arrowheads, A and B). Note that the stenosis of M1 segment is more severe in the left middle cerebral artery than in the right (white arrows, A and B).

Discussion

It is vital to recognize focal motor seizures and situations related to hyperventilation in children who present at the ED with a seizure. The former implies a structural lesion in the contralateral frontal cortex, and the latter predisposes children with preexisting vasculopathy to cerebral ischemia [8]. In the present case, the recognition of a focal motor seizure prompted neuroimaging, and excessive crying might have incurred or aggravated the cerebral ischemia.

In MMD, a focal motor seizure indicates a localizing sign. Seizures as a symptom of childhood ischemic stroke tend to be focal and accompanied by hemiparesis [9], and 68% of seizures in patients with MMD were focal [3-7]. Despite the relatively high frequency of focal seizures in MMD, it may be difficult to recognize a focal seizure and perform neuroimaging in toddlers who present at the ED with a seizure. Focal seizures are rarely witnessed, and account for the relatively low proportion of seizures in the ED (approximately 5%‒11%) [10,11]. Toddlers who have a focal seizure with fever can be misdiagnosed as having a “febrile seizure” owing to the high frequency of febrile seizures (range, 2%‒5% of all children)[10]. Sedation requirement may contribute to the reluctance in performing neuroimaging.

In this case, some other features are notable. Situations related to hyperventilation lower PCO2, provoking cerebral vasoconstriction [3,8]. A possible provocation of cerebral ischemia by crying may be supported by the temporal relation between the crying, the ictal episodes and the detection of acute respiratory alkalosis at presentation. It is worth noting that crying is a common provoking event in toddlers with MMD [3]. The boy was younger than the median age (6‒8 years) of children with MMD [12,13]. The age younger than 3 years is associated with seizures as a presenting symptom of childhood ischemic strokes, such as MMD [3,9,14]. A prospective study shows the association of the age younger than 3 years and poor prognosis of MMD [15]. The boy’s postictal hemiparesis that persisted longer than Todd’s paralysis, which typically resolves within 48 hours, implied that the stroke was the cause of seizure [16]. The RNF213 heterozygote c.14429G>A (p.R4810K) variant, which is strongly associated with MMD in East Asia, was detected [17]. This genetic feature suggests that family history may facilitate the diagnosis of MMD, especially in East Asia.

Children with MMD can present with a focal motor seizure, and situations related to hyperventilation can provoke cerebral ischemia in such children. Recognition of these features in the ED may streamline the diagnosis of MMD, a treatable cause of childhood ischemic stroke.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Acknowledgements

No funding source relevant to this article was reported.