소아에서 과산화수소에 의해 발생한 직장결장염

A case of hydrogen peroxide-induced proctocolitis in a child

Article information

Trans Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide is a strong oxidizing agent widely available as disinfectants. It can be harmful if it enters into the bowels. Within moments after gastrointestinal exposure, the colon becomes distended with reduced blood flow. The reaction with catalase can cause acute colitis due to the release of oxygen. We present a case of a child with hydrogen peroxide-induced proctocolitis.

Introduction

Hydrogen peroxide has antibacterial effects, and is frequently used to disinfect wounds and devices. However, when the colon is exposed to this chemical, reaction with catalase can cause acute colitis due to the release of oxygen. Symptoms include abdominal pain, hematochezia, diarrhea, and tenesmus. Colonoscopy findings of this condition, including white plaques, erythema of the surrounding mucosa, and multiple ulcers, are similar to those of other causes of colitis, such as ischemic colitis. Therefore, the differentiation is essential. Although several cases of hydrogen peroxide-induced colitis have been reported [1-8], there is a lack of relevant reports in children. We present here a pediatric case of hydrogen peroxide-induced proctocolitis with a literature review. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2019-11-042).

Case

An 8-year-old boy reported pruritus in the anus and perianal region. For symptom alleviation and disinfection, his caregiver performed enema using 3 mL of 3% hydrogen peroxide. One hour later, the boy complained of intermittent lower abdominal pain, tenesmus, and more than 3 instances of bright-red hematochezia, and visited the emergency department. Upon this visit, he appeared not sickly, and had no specific past medical or family history.

The initial vital signs measured at the emergency department were as follows: blood pressure, 120/80 mmHg; heart rate, 78 beats per minute; respiratory rate, 20 breaths per minute; and temperature, 36.8°C. Physical examination showed increased bowel sounds and tenderness on the lower abdomen. Initial laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin, 13 g/dL; white blood cell count, 10,300/mm3; platelet count, 372,000/mm3; prothrombin time, 13 seconds; and activated partial thromboplastin time, 36.2 seconds. The results of the peripheral blood test for electrolytes and biochemistry, and urinalysis were within normal limits.

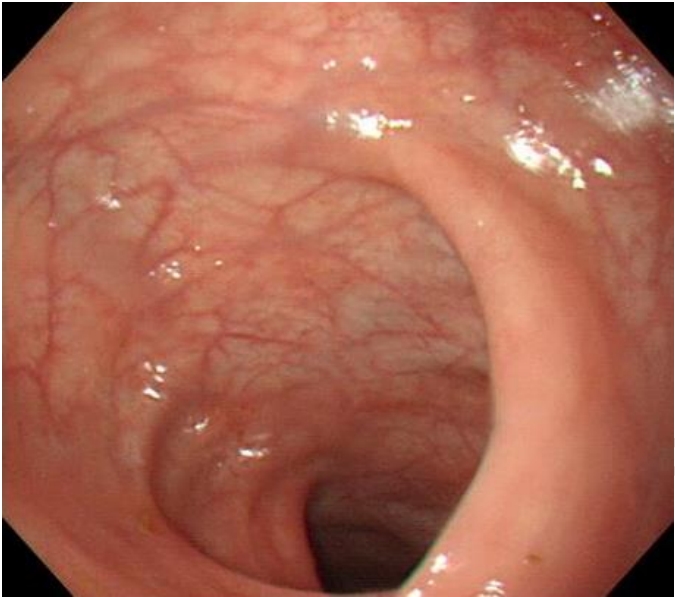

Chest and abdominal plain radiographs revealed no specific findings. Abdominal computed tomography suggested proctitis (Fig. 1), and subsequently he was hospitalized. On the same day, sigmoidoscopy was performed without colon cleansing. The findings showed severe erythema and edema in the surrounding mucosa, and small diffuse ulcers (Fig. 2).

Coronal scan of abdominal computed tomography showing the thickened and prominently enhanced rectal mucosa without signs of bowel perforation.

Initial sigmoidoscopy finding showing the discrete white plaques adherent to severe erythema of the surrounding colonic mucosa, patchy granularity, and scattered ulcers (up to 10 cm from the anal verge).

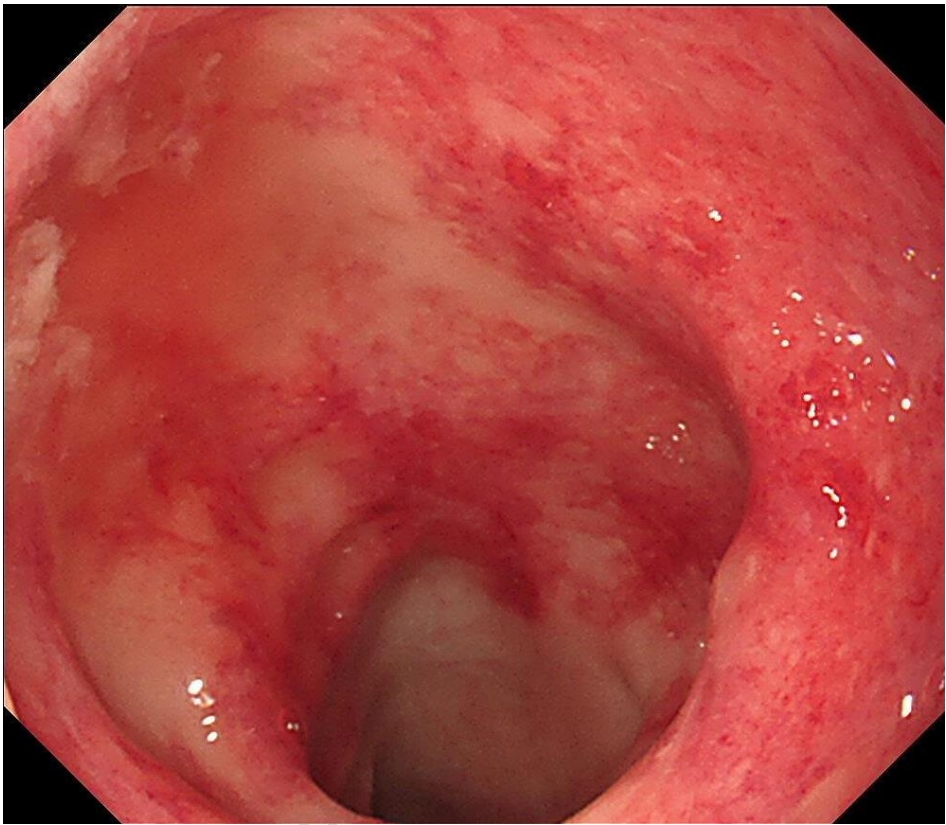

Conservative therapy was performed with nil per os, fluids, and parenteral nutrition. The abdominal pain and hematochezia were alleviated on days 2 and 3, respectively, and then he started an oral diet. On day 5, he was discharged uneventfully. One month later, the lesions on admission sigmoidoscopy disappeared on a follow-up sigmoidoscopy (Fig. 3), and no complications developed.

Discussion

Hydrogen peroxide is the simplest peroxide that is a compound with an oxygen-oxygen single bond. Its chemistry is dominated by the unstable peroxide bond. The pathogenesis of hydrogen peroxide-induced proctocolitis may be secondary to a chemical reaction (2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2), resulting in penetration of highly reactive oxygen species, which incur damage to the colonic mucosa. Hydrogen peroxide solution permeates into the tissues where it reacts with catalase to release oxygen. Soon after the exposure, the colon becomes distended with reduced blood flow, and rapidly leads to molecular denaturation, causing bleeding, ulceration, and necrosis [9]. Blanching occurs as hydrogen peroxide contacts catalase within the capillaries and forms microbubbles of oxygen, which impede blood flow. If the bubbles enter the large veins or lymphatics, a fatal air embolism can develop [10,11]. According to the report by Sleigh and Linter [12], among patients with perforation of sigmoid diverticulum and abscess formation, some developed cyanosis and tachycardia after 200 mL of hydrogen peroxide solution was used to wash an abscess below the fascia lata. Similarly, Bassan et al. [13] reported a near-fatal air embolism after the use of hydrogen peroxide solution to wash the enclosed body parts. In some previous studies, most patients exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide showed mild gastrointestinal symptoms, but developed hematochezia, lower abdominal pain, and tenesmus, and then recovered from a transient injury [14,15].

Shaw and Danis [16] reported that after a canine colon was washed with 0.75% hydrogen peroxide, the partial pressure of oxygen in the portal vein was 10 times higher than normal values. With regard to chemical colitis caused by colonic lavage with a disinfectant, some authors have artificially induced ulcerative colitis in the rats. Mann et al. [17] and Mann and Demers [18] used colonoscopy to monitor colitis for 8 weeks after intracolonic administration of 10% acetic acid to mice. In these experiments, ulcers appeared at 24 hour, and histology showed infiltration of inflammatory cells to the mucosa and submucosa, crypt abscess formation, and congestive necrosis, and these lesions lasted for 8 weeks [17,18]. In the present case, colonoscopy showed mucosal edema with shallow ulcers distributed from the anus to the sigmoid colon. The occurrence of mucosal lesions might be due to the following mechanism. After oxygen is produced as hydrogen peroxide solution permeates the epithelium and capillaries, blood within the capillary is forced into the intramuscular vessels where it is substituted for oxygen by tissue catalase.

Colitis caused by disinfectants is uncommon. Thus, cases of hydrogen peroxide-induced colitis in children are rarely reported, and therapeutic plans for the colitis are not yet defined. However, as shown in this case, conservative therapy, such as fluid therapy, can alleviate symptoms without sequelae. Uses of prophylactic antibiotics, steroids, and mesalazine have also been reported [4,8,19,20]. Considering the lack of clinical knowledge about hydrogen peroxide-induced colitis in children, it may be necessary to establish treatment guidelines based on the exposed dose per body surface area and the extent of mucosal injury. This case report will be helpful in establishing the guidelines.

This paper described a pediatric case of hydrogen peroxide-induced colitis after the use of hydrogen peroxide enema solution with the endoscopic findings. It brings to attention the danger of the improper use of hydrogen peroxide-containing pharmaceuticals to prevent complications.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Acknowledgements

No funding source relevant to this article was reported.